- Home

- Olivia Newton-John

Don't Stop Believin' Page 2

Don't Stop Believin' Read online

Page 2

‘Use mine,’ Hess said, offering Dad a Luger that he had hidden in his clothing! Of course, it didn’t set off any metal detectors in those days.

A different time!

My parents might have never met at Cambridge University if my mum didn’t have such a keen ear for beautiful music – the kind that could melt your heart. One day, she heard a man singing in a deep baritone voice and she couldn’t take another step. She actually followed the voice. Mum always said she fell in love with the voice first before she even saw him. They were the same age, seventeen – young and full of dreams. Mum was brunette, classically beautiful, and carried herself in the most elegant way. Dad was six-foot-three, fair-haired, with movie-star good looks and that beautiful aristocratic voice. Need I say more? What a beautiful couple.

You could call it love at first listen, and then sight. It wasn’t too long after that they were married, and in a blink, my brother Hugh (destined to be a doctor) was born, and then my stunning sister Rona (future model, actress and singer). I was the youngest of the three, born eight years after Rona, and apparently the ‘try to save the marriage’ baby – but more on that in a moment.

Before I was born, my mother went through some very difficult times. My father was away serving in World War II at Bletchley Park, working on the Enigma Project, and she was left alone with two young children. She was a beautiful German woman, and the villagers were suspicious of her. Two kind Quaker women would bring eggs and vegetables to her doorstep to help her and the children. They were her only friends. In turn, Mum would speak kindly with the German prisoners of war. One of the many things my mother taught me was that no matter what you’re going through in life, kindness is what will sustain you.

Not everyone was kind, though. Later, Rona would tell me that our father had an affair while he was in the Air Force. One day, a woman came knocking on my mother’s front door to tell her about it. It left my mother insecure and untrusting, not to mention broken-hearted, as she had loved my father since she was seventeen.

To her credit, she stayed in the marriage and tried to make it work for the good of the entire family. Forgiveness was another thing she would teach me, the make-up baby, who would be her last child.

My father was charming, charismatic and devilishly handsome, and demanded the best from himself and his family. A ‘well done’ was a compliment of the highest order from him, and not easily attained. Dad believed in hard work, discipline and doing things on your own merits. For example, he could have easily arranged for my brother to get a free pass into university, but he insisted that Hugh excel at his exams and earn his own place. And, of course, Hugh was amazingly brilliant and did it. My brother, in fact, graduated as a doctor with honours. He went on to be a specialist in infectious diseases and invented the first portable iron lung. As I’m writing this I’m thinking, Lucky I can sing! Thanks, Dad, for the musical genes.

When I was a little girl, Dad would sing out loudly in church, but I was embarrassed by it because I didn’t want to be noticed. He had a wonderful sense of humour and would tease me by pretending to be a really old man, crinkling his fingers and speaking in a creaky voice. I laughed and laughed.

I adored my father and think more about him now than ever before, especially when I hear classical music, which was always playing loudly in our house. I close my eyes and see my father busy conducting each note as he smiled and drank his evening sherry.

For many years after they divorced, I couldn’t even listen to classical music and neither could my mum – it would make both of us cry. Years later, I would find my mother sitting in a chair with beautiful classical music on the radio and tears in her eyes. I knew she was thinking of my father. She was in her eighties at the time.

I’ll never forget when she turned seventy. Dad, who had been married twice more since their union, sent her seven bunches of violets, one for each decade.

They were her favourite flower.

When I was a young child, we lived in England where my father was headmaster of King’s College in Cambridge. I have very few memories of that time besides crawling around on a thick blue carpet between my parents’ twin beds in their bedroom. The sleeping situation was quite the norm for those days. They were like the English Lucy and Ricky!

Of course, I was a young child and full of energy, so there were a few unfortunate moments, including when I swallowed a bunch of sleeping pills by mistake. I had to have my stomach pumped, and the whole experience was so mortifying and memorable that no wonder drugs of any kind have never interested me again.

I was perfectly willing to go on other types of adventures, though. When I was quite little, I stood on a stool in front of the bathroom mirror with a thermometer in my mouth because I suddenly needed to take my own temperature for reasons unknown. Not knowing what to do, I bit straight through the glass and soon found the mercury rolling around my tongue. It was at that point that I decided to involve a responsible adult, and my actions caused my parents a good deal of alarm, though I was no worse for wear.

Most of the time I was a good little girl, except for the occasional misstep. Later, when I went to school in Australia, we had a weekly Bank Day where we would take money to school and they would put it in the bank for us. It was a lovely discipline and I did take money to school, but instead of saving it I used it for a current need: to buy everyone a lolly. I thought I was being kind! Sadly, the headmaster at my school had other ideas. In quite a stern voice, he called me up to the front of the class, and embarrassed the hell out of me.

‘Olivia Newton-John!’ he boomed. ‘Where is your money to put in the bank? What about your future?’

What future? I was five!

I put my hand in an empty pocket of my little pink dress and explained the ‘lollies situation’. This wouldn’t be my only punishment. On my way home that day, the big force of nature and former MI5 agent that was my dad intercepted my tricycle and pulled me the rest of the way home. (Oh, big, big, big trouble was brewing!)

My headmaster had called him and Dad was very upset, but not for long. Thank goodness my big sister Rona was always a beautiful free spirit who defied authority – she made for a perfect diversion.

That night, she took the heat off my foolish ‘crime’ with her own antics. She had been expelled from school for wearing her school uniform skirts too short and bleaching her hair. She also skipped school to meet with boys.

I was off the hook!

In the mid-fifties, our lives took a dramatic turn, one that would mould my psyche. We were migrating to Melbourne because my father had accepted the coveted position of Master of Ormond College at the University of Melbourne. He was the youngest man, at only forty, to ever receive a position of this kind. I was five years old when my parents, Hugh, Rona and I boarded a massive ship called the Straitharde to cross the ocean to Australia.

Even at that young age, I was so very proud of my father because he was up against older and more experienced academics for this important position. Dad had written a letter to the Dean, explaining how he wanted to introduce his family to the amazing country of Australia – and he got the job.

That can-do spirit runs deep in the Newton-John family.

Professionally, it was the chance of a lifetime for my father, and personally, it was an opportunity for my parents to create a new chapter in their life together. They were fighting a lot before we moved and thought a change of scenery could provide a fresh start.

My only memory of the ocean voyage from Cambridge to our new life in this place called Melbourne was losing my favourite teddy bear, ‘Fluffy’. I was broken-hearted because I loved Fluffy, but my parents replaced it with a stuffed penguin named Pengy (so creative!) that they found in the ship’s store. It was never quite the same, though. Some things are irreplaceable, as I would soon find out in much bigger ways.

It wasn’t long before we were in a new country and unpacking boxes at our fantastic new home on campus, a beautiful stone mansion with endless bedrooms a

nd our own housekeeper. I couldn’t believe my eyes as I navigated those long hallways that were perfect for hide and seek. There were so many big rooms to explore, and it all fed my imagination. One day I was a princess in the castle; the next, an explorer. There were no limits.

We were required to live on the Ormond College grounds so that my father was accessible both day and night. No one minded because it was such a safe and lively atmosphere and, in many ways, I considered it a giant playground. Ormond was a place of old vine-covered buildings and rolling green lawns that gave me plenty of exercise. And I never got lost because there was a steep clock tower in the middle of campus that served as my compass.

As a little girl, I loved watching the students find the fun in their college days. I remember ‘water bagging’, where the undergrads would drop bags of water out the windows of their bedrooms onto the unsuspecting heads of the people walking below. If you looked up, you’d get a face-full of cold liquid, right between the eyes. I probably got hit by accident, but then again, I liked the excitement and the dare of looking up!

‘You’re soaking wet!’ Mum would say when I walked in the door from a day at the Melbourne Teachers’ College training school (where we literally had new teachers practise on us every month).

‘Yes, Mum, I am!’ I said with glee.

At night, I could hear the young men who had won their rowing competitions banging their spoons on the solid wooden tables in the huge dining room as they enjoyed their meal looking up at the gorgeous stained-glass windows. The dining hall was adjacent to our house. Years later, when I visited Ormond to see my father’s oil portrait hanging there, I saw all those spoon dents from years of celebrations – it brought back great memories.

My favourite activity was sitting outdoors on the steps of a beautiful old stone building where I would wait for my father to finish work for the day. There I was, a six-year-old girl in her school uniform – a blue and white checked dress with little brown shoes and white ankle socks. I’d visit with the birds and trees, smell the fresh blooms, and write poetry while waiting to slip a small hand into his bigger one.

Our home had a huge drawing room where my parents would entertain important university types such as visiting professors or other university presidents or even government officials who helped raise money for the school. I’d hide in a little alcove halfway up the stairs, watching the beautiful people arrive for lavish catered cocktail parties.

From my vantage point, I could see my mother in a gorgeous red velvet evening dress with hundreds of tiny covered buttons up the back. It was so glamorous and exciting. She would greet each person in her refined and regal way, and then she and my father both always made time to come upstairs to kiss me goodnight.

If I was allowed downstairs, I’d go to work lighting people’s cigarettes. For some reason, I liked the smell of the sulphur of the match and the burning tobacco and paper. My father used to smoke when he was reading me a bedtime story so I must have associated comfort with smoke, although now I know cigarettes and second-hand smoke are toxic for your health. No one really worried or knew about it in those days, of course. In fact, doctors would tell you that smoking was relaxing and good for your health. (Can you even imagine!)

One of my parents obviously had a sixth sense about future discoveries. One night, Mum saw me lighting cigarettes at a university function and pulled me aside.

‘Well, darling, why not try a whole one?’ she suggested, handing me an entire package of cigarettes.

I was nine and thought this was a splendid idea. How amazing that Mum would allow me this ‘treat’ at my age! I sparked up a cigarette.

‘Why don’t you take a deep puff?’ Mum instructed.

I was excited and complied – only to cough violently for what seemed like forever. ‘I never want to smoke again!’ I cried.

Yes, she was a really smart mum.

Years later when my friend Pat and I were living in London and singing together, I would try to take up smoking again. We had a crazy notion that smoking would give us sultry singing voices like our favourite singer, Julie London. Alas, sultry wasn’t on the cards for me because I was still that nine-year-old in her PJs. Later in my life, in my Sandy nightie, I would try to smoke on screen in Grease and became that little girl again hacking away.

Art imitating life!

I can still remember my father’s smoke lingering on the sleeves of my pink cotton PJs. I’d go to sleep smelling him with my nose pressed to my pyjama sleeve, which was sadly an experience I wouldn’t have for long.

Our home looked perfect from the outside, but inside was another story. When the newness of moving to another country turned into sameness, my parents’ marriage began to deteriorate again. I knew because Mum and Dad took separate holidays, although they tried hard not to make an issue of it.

I remember nature-loving Mum taking us children camping in Mallacoota, in a field near the beach. One afternoon, we went out to fish for our dinner and a few runaway cows wandered over to our tent and trampled everything – except a can of condensed milk with a cow’s face on it! Mum could only laugh, and we were crying tears because it was so funny. Mum had a keen sense of humour and could make something amusing out of anything. I loved her spirit! She even managed to laugh when I was being taught how to fish and accidentally caught my brother’s mouth with the hook!

When I was about nine, my parents announced that they were designing a beautiful new house for us to live in on the Ormond property. Sadly, we would never sleep a night in it. One evening after school, my father calmly told me, ‘Your mother and I are going to live separately and you will go and live with her.’

‘What about the new house?’ I asked through a veil of tears. ‘Are you . . .?’

I didn’t want to say the words.

I didn’t want to believe it.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘We’re getting a divorce.’

‘But I want to live with you,’ I pleaded as tears raced down my cheeks. It was the most painful moment of my young life, made worse when my father shook his head with a finality that indicated my living conditions had already been settled.

‘You can’t live with me,’ he said. ‘It’s better if you live with your mother. But you can still see me every day.’

In a blink, my young life was turned upside down. Mum and I did move, to an apartment not far away in Parkville. It was going to be harder to see my father now.

It got worse. Eventually, Dad was asked to leave his post at the college because the administration was strict about needing a married man at the helm. He was no longer traditionally ‘married with children’.

It was so sad because Dad loved Ormond College, and he’d made the school co-educational, allowed alcohol for the first time on campus and was a very popular headmaster. But rules were rules and they made him leave because he was now a divorced man, which was strictly forbidden. Given no choice, Dad moved to Newcastle, a two-hour flight away, where he worked as a vice chancellor and taught German. This marked the end of any hope of even weekly or monthly visits, as they were too expensive on his academic salary.

My heart was broken.

Mum wouldn’t be around as much during the days either, as she had to support us on her own for the first time in her life. In those days, women didn’t fare very well in divorce settlements, and watching my mother struggle financially taught me how strong women rally to take care of themselves and their children. Mum had never worked outside the home, but she was funny, witty and intelligent. She had other valuable skills, too. She wrote beautiful poems and would regularly write letters to the editor of our newspaper about local issues.

It makes me sad now because my mother was always very interested in science, but was dissuaded from following that path. Women weren’t encouraged to go into academia in those days, and this was a particular shame given her father’s scientific past.

Luckily, Mum quickly got a job, located in the tallest structure in Melbourne at the time called the IC

I House. It was Australia’s first skyscraper, and it felt exciting when she left each day for her work as a receptionist. We were all proud of her for making ends meet – Dad didn’t have a lot of money to spare, but he sent what he could scrape up to help the two of us. My siblings were out of the house by now and Rona was even married.

It was just us two.

We could only afford for me to see my father at Christmas. During these two months off, I spent as much time as possible with him and the three daughters of his best friend, a Welsh professor, Harry Jones. One of them, Shahan, brought some much-needed joy to my life because she had a beautiful chestnut horse with white socks named Cymro, which means ‘friend’ in Welsh. It was sheer bliss for me to ride every day with her. My father even rented me a horse of my own, so we could ride together.

Oh, how I loved my beautiful shaggy pony named Flash. He was anything but just a loaner. I adored him.

Mornings when my father was busy meant Shahan and I could ride to our hearts’ content, followed by picnics with her sisters and then swimming with the horses at the beach and in the lagoon. Tired, but happy, I would come home and tell my father that I didn’t want to take a shower that night.

‘I want to smell like my horse!’ I informed him.

My fondest wishes in those days were that my father would return home, and that I could bottle that musty scent of my horse laced with the worn leather of the saddle.

I loved those summers and cherished every moment, including when my father fell in love with a wonderful woman named Val, who was the university librarian and a very accomplished pianist. She would play piano and Dad would sing. They eventually married, which gave me a loving new brother, Toby, and new sister, Sarah. From the start, I adored them all.

I’ve never liked the word ‘step’ when attached to family members. It has a bad connotation – like Cinderella or something!

One of the most beautiful lessons I learned at this time was from my mum, who combined kindness with forgiveness. When my dad had children with his new wife, she sent gifts for the babies.

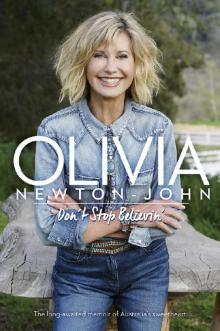

Don't Stop Believin'

Don't Stop Believin'